Takin’ It to the Streets: Pilgrimage in East Lansing

By Amy DeRogatis

Last Sunday, April 2, 2017, I participated in an interfaith pilgrimage through the streets of East Lansing. To prepare for the event, I spent a few days reading and thinking about pilgrimage. Why do people take pilgrimages? What do they hope to accomplish? Where are they seeking to go? And, significantly for this project, what are the sounds that I might expect to hear while on a pilgrimage?

A pilgrimage is both a physical and spiritual journey. Pilgrimage is not simply a hike by like-minded people to reach a destination. It is a devotional sojourn. The physical process of moving through space is an embodied affirmation of religious beliefs and values. Religious studies scholar S. Brent Platt notes: “In pilgrimage, the body-soul distinction becomes irrelevant: souls and soles are not just homophones.” He explains that pilgrimage brings “religion to its senses, in ways more fundamental than the abstract studies of doctrines and texts. At the heart of religion, there are bodies: breathing, sensing, feeling, and interacting with natural environments, human-made objects, and other bodies” (Introduction, “The Varieties of Contemporary Pilgrimage,” CrossCurrents, Vol. 59, No. 3, Sept. 2009, pp. 266, 267). Along the way, the pilgrims walk together or separately; they are simultaneously in a group procession and they are individuals on their own paths.

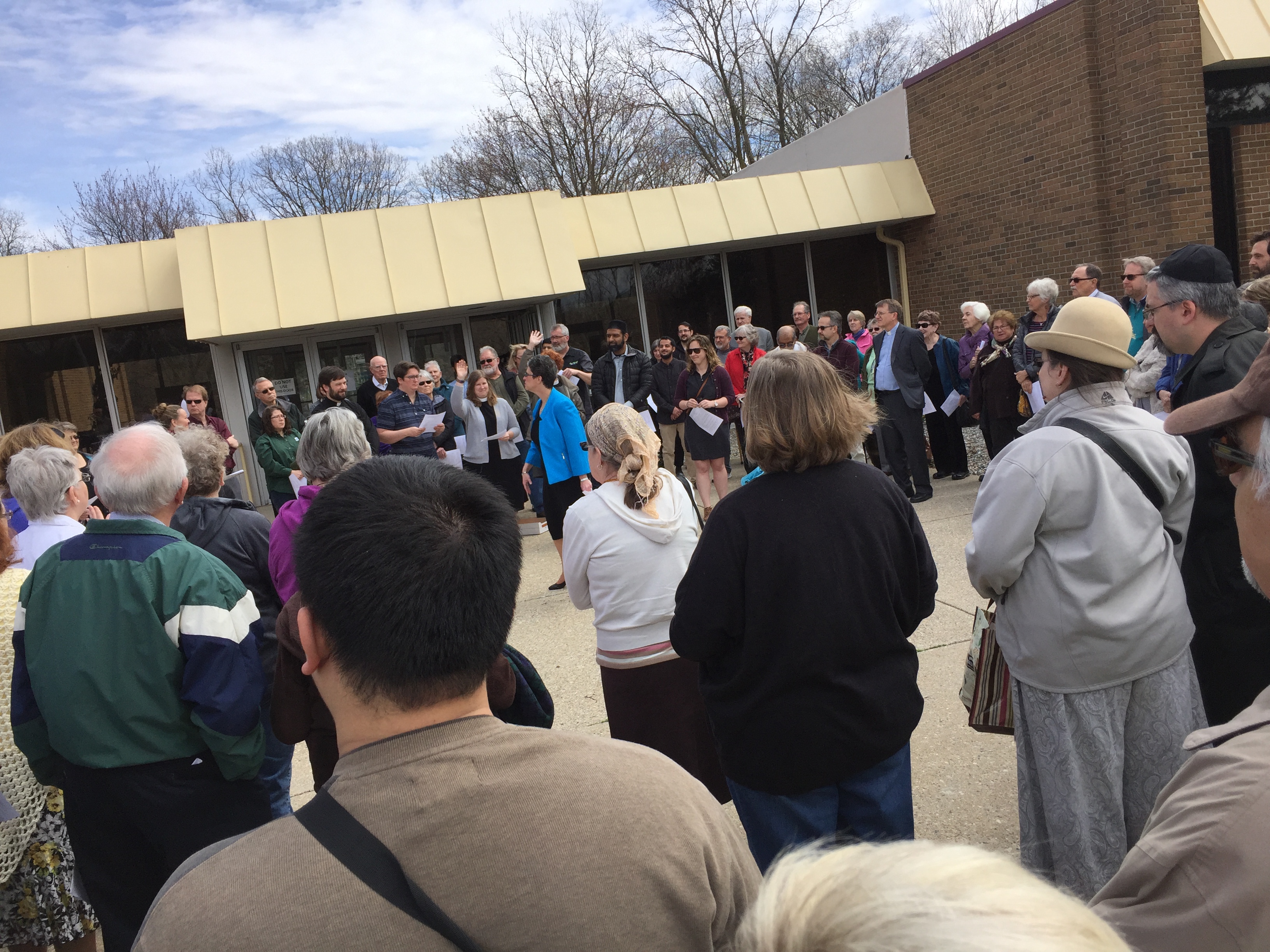

At Shaarey Zedek, explaining the meaning of pilgrimage:

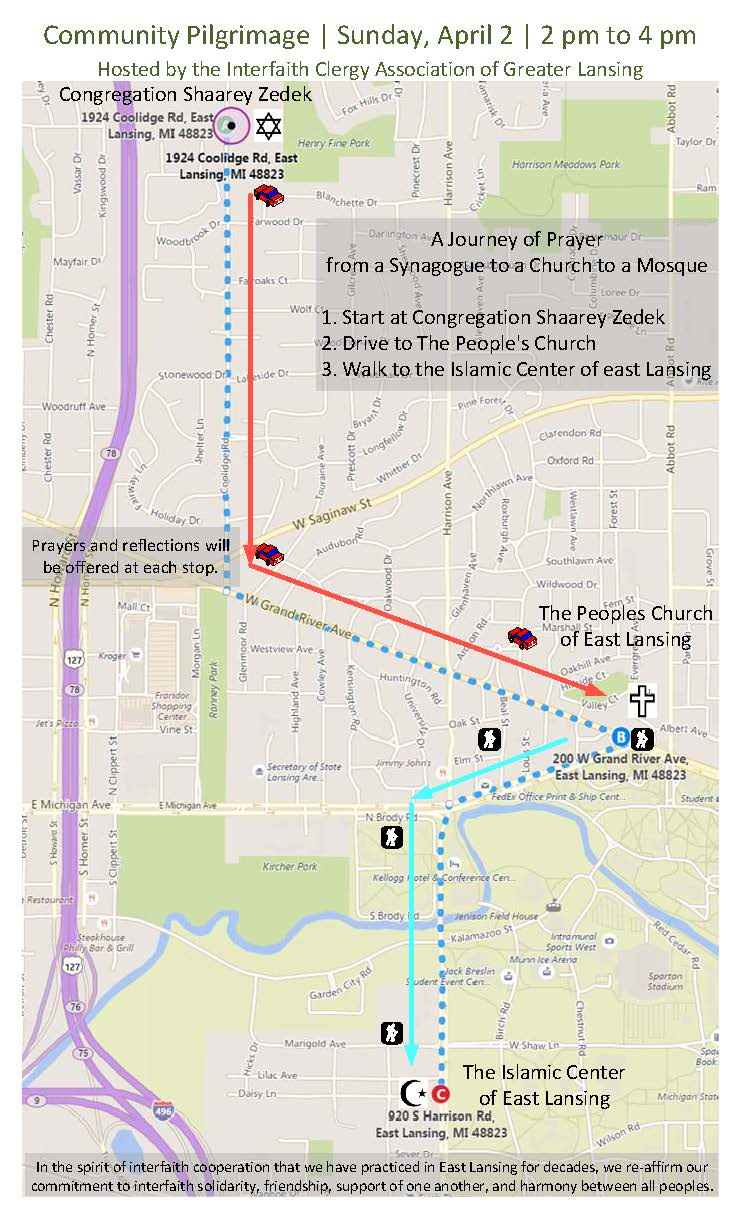

Pilgrimage to sacred sites and people is an ancient spiritual practice common to many religious traditions. Not unlike the ritual of gathering for communal meals, pilgrimage is a practice that has deep roots in many faiths including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the three religious traditions most clearly represented in the interfaith pilgrimage through the streets of East Lansing. The route of the pilgrimage was drawn to affirm the connections between those three faith traditions. We began at congregation Shaarey Zedek, then drove to the Peoples Church, and then walked with a police escort to the Islamic Center of East Lansing. At each stop, we heard prayers from all three traditions.

Rabbi Amy Bigman at the Peoples Church:

At the midpoint, we listened to the children’s choir from the Islamic Center sing “America the Beautiful.” At the center of the physical and spiritual journey was the acknowledgement of communal identity as citizens in a particular time and place.

The children’s choir singing at the Peoples Church:

Incorporating a civic song into a religious practice performed in public outdoor space reminded me how difficult it is to define a religious sound. Is singing a civic song by a faith-identified choir a religious sound? When the sounds from the choir were heard in the parking lot of the nearby coffee shop, would they be recognized as religious? Did the people who jogged by our gathering have the ability not to engage with the religious practice as the sound spread through the public space? These are things that I was wondering as we walked down Grand River Avenue. Not only was our procession being seen; we were being heard. While the pilgrimage had spiritual significance for the people who chose to participate, it also made the faith practice public for anyone who happened to be on the street. When I asked the person walking next to me if it seemed important to her that we be seen and heard, she confirmed that was, for her, a significant aspect of the pilgrimage. That is why at each stop on the journey we remained outside, visible and audible to our community.

The anthropologist Matthew Engelke, who thinks and writes a lot about religious practices in public spaces, explains that being religious in public is not always about grand gestures, but often happens in small instances of being part of the background noise in public places. For example, he examines the practice of Bible study groups meeting in coffee shops to make the argument that Bible reading becomes part of what he calls “ambient faith.” By this, he means being part of the background noise of the public square. For Engelke, the practice of having a bible study group in a coffee shop–where anyone can overhear– collapses the distinction of public and private and expands the definition of religion. “ . . . [T]he production of ambient faith,” writes Engelke, “ . . . depends on at least two refusals: the refusal to accept the distinction between public and private when applied to religion and the refusal to be satisfied with the very idea of ‘religion’ itself.” (“Angels in Swindon,” American Ethnologist, Vol. 39, No 1, p 165). As we walked down the windy streets and chatted with each other about spiritual, political, and mundane topics, we were creating ambient faith. The sounds of religion in public were two mothers comparing notes on teenage daughters while on pilgrimage, as well as the communal prayer of St. Francis of Assisi competing with traffic noise outside of the local synagogue. The sounds along the route were simultaneously private and public; they were both sacred and profane.

“Let There Be Peace On Earth” at the Islamic Center of East Lansing:

Map of pilgrimage route: